Andy Edwards poses some questions to consider in the wake of the 30 Under 30 diversity discussion

This article first appeared in the Record of the Day weekly magazine, but can also be viewed online here.

If it’s not the Oscars it’s the BRITS, if it’s not the Billboard Power 100 it’s Music Week’s 30 Under 30, the question of diversity within the music industry has boiled to the surface this year. In 2016 this is deeply troubling.

Music Week’s front cover featuring 30 people under 30, initially nominated by readers, and then finally selected by MW, was the latest lightning rod for this topic. If the next generation of executives cannot be truly diverse, what hope is there?

One criticism leveled at Music Week is that editorial judgment should have been exercised and a broader list of names proactively sought. Instead, Music Week reported on the candidates whose names had been put forward. Judging by the list of 108 names that did not make the final 30, the total list put forward was overwhelmingly white.

Perhaps any attempt to disproportionately select candidates of colour would have masked the real story and a much broader underlying problem? Music Week did report the facts whether we like those facts or not.

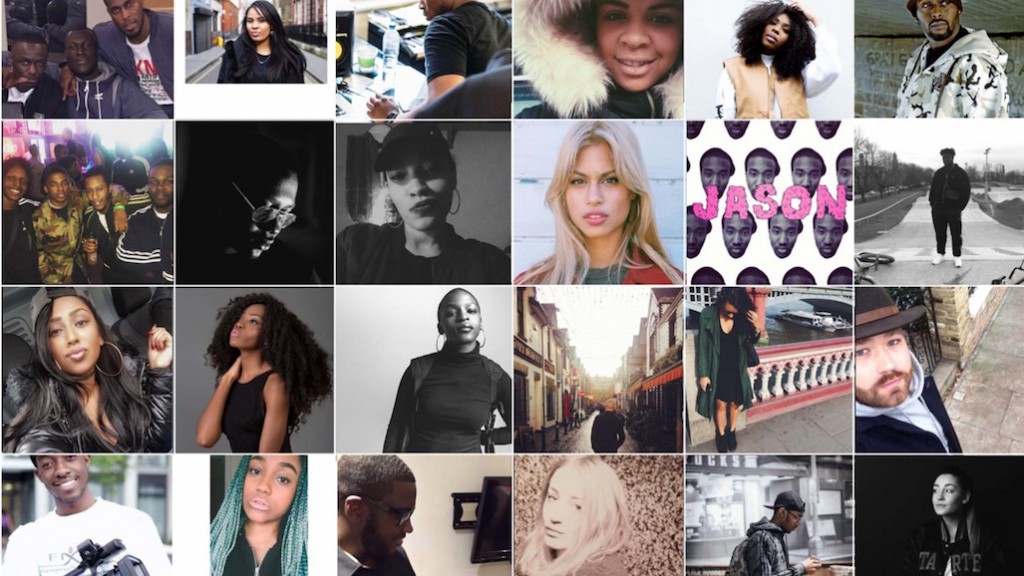

The counter list on Nation of Billions put forth by DJ Semtex is incredibly powerful. One person came up with 30 alternative names in a matter of hours, a list that was overwhelming diversel and brimming with talent. A further list from Complex made a similar point.

What interests me most of all right now is to understand what is going on and why. In very broad terms, it strikes me the Music Week list is made up largely of what we would consider to be the “traditional” music business, whether that is corporates or established PR and management companies.

In contrast, Semtex’s list – while containing quite a few major label people – skewed much more heavily to the self-starters, the entrepreneurs, those with portfolio careers and the emerging music businesses – the blogs, the YouTube channels, the club nights, and so on. The same was broadly true of the Complex list.

Compilers of such lists have to consider a much broader range of job roles than ever before and a much broader range of organizations and career paths. What constitutes the “music industry” itself can be debated at length.

If the music industry is to reflect the wider world, what is that wider world? The last UK census in 2011 revealed that 13% of the UK population is non-white, but in London that percentage rises to 40%. Undeniably the industry is still overwhelmingly London-centric, which places even more emphasis on diversity within our industry.

And what of the challenges of a London-centric industry? Moving to London was part of the attraction of being in the music industry, but with rents and property prices at an all-time high, does that also stifle diversity of a different kind? Factor in ever increasing levels of student debt and the problem multiplies. Some have said only the posh Home Counties middle class need apply – probably a blog post in itself!

So we as an industry need to ask ourselves some questions.

The Who and What Questions:

- Who does the industry employ? What are the numbers by ethnicity?

- What is the break down across sectors of the industry?

- What are the emerging sectors that should form part of the music industry?

- What are the ethnicity numbers by job role? Creative vs Business roles?

- Does music genre play a role in determining the spread of diversity?

- What are the conventions and processes that are restraining diversity?

The Why Questions:

- Why do some jobs attract a more diverse range of applicants than others?

- Why do people from certain backgrounds want to work in music?

- Why do people from certain backgrounds not want to work in music?

- Is the music industry attracting the right mix of people? What is the right mix?

- Why do employers recruit in the way that they do?

There is a lot of soul searching to be done. Perhaps we all have to ask questions about our own journeys, experiences and motivations in order to make those connections with others. We should constantly question and challenge ourselves.

I grew up in a small town in the north of England. I remember a kid in the playground calling me “Jew Boy” because I had curly hair, a big nose and my Dad worked for a bank. I didn’t know any Jewish people at the time, but I did know what it felt like to be different and I have always been appreciative and inquisitive of people’s differences.

Working in the music business was an opportunity to do something different. I like being around crazy people, but really I’m the commercially focused sensible one. At Sony Music in the ‘90s, I was a Marketing Analyst. No one knew what I did and I always had to explain. So a part of me jumped for joy that the first name on the Music Week 30 under 30 list was an Analyst from Sony Music.

As an indie kid from up north, Sony was also an opportunity to expand my knowledge of black music. With colleagues such as Semtex, Matthew Ross, Adam Sieff and others I filled up on hip hop, soul and jazz. I was clueless but I learned.

Moving around the industry, one learns about the differing professions and tribes. You listen, learn and absorb. As the industry grows more complex a broader range of skills are required. It also means opening one’s eyes and ears to those with different backgrounds, experiences and perspectives.

But this runs counter to the way in which the industry has traditionally organized itself. The “its who you know” mantra is self-selecting. A female colleague describing an iconic label she worked at recalled, “there was a certain type of person and you either fitted in or you didn’t”. Like attracts like.

On another occasion, when interviewing for an assistant role for a colleague, one candidate spoke enthusiastically about some work they had done for their local church. Afterwards, my colleague remarked “hummm, bible basher”, completely misunderstanding the background and culture of the candidate. Clue: 48% of London’s church-goers are black.

Some organisations deploy more sophisticated recruitment techniques such as competency based interviews or algorithms yet many tech companies have diversity challenges also. These techniques can also be self-selecting and if candidates are not attracted to certain industry sectors or roles, one has to ask “why?”

This is not an easy process, whether that is on a macro level or a mirco level. Relaying back to personal experience, the best and most productive working relationships have always been those where I have worked with someone who is the polar opposite to myself. That might not necessarily make for an easy experience but it is always exciting, challenging and most of all delivers exceptional results.

The music industry has to grapple with a much bigger picture on a macro level. It is not just music; other creative sectors such as film, TV and publishing are facing similar issues. It seems no one is handling this well.

This is a topic that is already being hotly debated at UK Music board level for some time. The senior figures within our industry are already deeply concerned and are seeking to understand the issues and challenges, including some of the questions I have raised above.

There will be outreach, through UK Music and its members: the BPI, AIM, MPA, PRS, MMF and so on are all intending on surveying their memberships. Ged Doherty and Keith Harris are looking at this issue specifically. I would ask anyone reading this article to engage and retweet and spread the word. There will be more announcements to come. Watch this space and get involved.