Andy Edwards explores the facts and figures behind the Arts Council v Music Business debate. This article first appeared in Record of the Day.

The role of the Arts Council is once again in the headlines. This week, leading figures representing the music industry locked horns with senior opera figures over Arts Council funding.

UK Music CEO Michael Dugher branded Arts Council England (ACE) “too posh for pop”, pointing out that 62% of ACE’s National Portfolio goes to opera and a further 23% goes to classical music. In contrast, only 8% goes to popular music and 7% to other genres (including jazz, folk, etc).

Hitting back in The Daily Telegraph, Michael Volpe General Director of Holland Park Opera, responded “I’ve been hearing the word ‘posh’ in relation to opera for 30 years. Very few people in opera are posh – certainly not the performers”, although Volpe conceded in the same piece “Opera companies get a lot of money, perhaps more than they ought to, and that’s an ongoing argument.”

ACE has £1.45 billion of public funds and £860 million National Lottery funds to distribute over the next four years. Of the £368 million allocated to music, opera will receive £229 million, classical £85 million and pop £27 million.

The debate is especially timely because ACE has initiated a public conversation to help inform its strategy for the next 10 years. Given the music industry is only just returning to growth having suffered 15 years of decline, a lot is at stake. A barrier to that discussion is a fundamental misunderstanding between both sides.

Some might argue the opera world, and the arts establishment as a whole, seem to look down on the music industry or, perhaps, hold the view that it is less deserving. Many in the music industry consider opera an irrelevance and an extravagance.

The reality is the music industry is vastly more complex, diverse and challenging than is often understood. It is also a reality that opera is accessible through multi-tiered ticket pricing and many opera companies are addressing their own diversity issues.

What are the key issues? How can both sides better understand one another and what does a satisfactory outcome look like?

THE FUNDING IMBALANCE

Not only is there a huge imbalance towards opera, but there is also a disproportionate amount awarded to the Royal Opera House in London specifically. During 2016 alone, the ROH received £28 million in Arts Council funding, which represents 20% of the ROH’s total income for that year. The remainder is made up of box office receipts, commercial income and other fundraising. This includes various charitable trusts and corporate backers such as Goldman Sachs.

By way of comparison, UK Sport fulfils a similar function to the Arts Council and also relies on a combination of public money and lottery funding. It is worth noting the spread of investment across the Olympic disciplines is much more even. Of the £265 million earmarked for the Tokyo Olympic cycle, rowing receives the most with £32 million, followed by athletics (£27m), sailing (£26m), cycling (£26) and swimming (£22m). Although medals success and underlying costs are a factor, the distribution of funds is far more even when compared to arts funding for music. Equestrian was further down the list with £15m, but imagine the uproar if Equestrian took 60% of available funding at the expense of other medal winning sports.

It is hard to see how the imbalance between opera, classical and other forms of music can be justified. Moreover, if funding were to be taken away from opera and distributed more broadly, how detrimental would that be? Supposing ACE funding for the Royal Opera House is cut in half, that would represent a 10% cut in its overall income. Can the ROH be challenged to go without or make up that funding elsewhere?

MOMENTUM MUSIC FUND – A CASE FOR GRANT FUNDING

In 2013, Arts Council England supported the launch of the Momentum Music Fund, administered by the PRS Foundation. Momentum was aimed at artists existing outside the major label system, unsigned or signed to an independent, and who could demonstrable a case for £5-15,000 worth of funding to give their careers tangible momentum at a crucial point.

The scheme has been a great success. Over 270 artists have been supported by Momentum and for every £1 invested £7.46 has been generated. Recipients are truly diverse covering a broad spread of genres with a strong BAME representation, making up 49% of grantees.

Over 3,800 artists have applied for Momentum funding since its inception. Five years after its launch demand and impact has never been greater. The recently published outline of Government’s creative industries sector deal, which encourages partnerships between government and industry, mentions the Momentum Fund as an example of good practice.

The frustration is that despite this clear proof of concept, including the quality and diversity of the artists supported and the match funding & income it has leveraged there appears to be little appetite from the Arts Council to continue its involvement in such schemes.

ATTITUDES TO INVESTMENT NEED TO CHANGE

A key challenge is how the music industry is perceived and how it perceives itself.

Culturally, a disproportionate level of attention is afforded to a tiny minority of major artists earning vast sums at the expense of the majority who do not. This contributes to long held assumptions within the arts establishment, government and the wider public that all paths through the music industry are paved with gold. They are not.

Within the industry itself, there has been a tradition of self-reliance. Labels and publishers, especially, pride themselves on their investment in new music. This is very true, but that investment only comes at a certain stage. Leading up to that point, artists and their managers typically funded themselves. Prior to the launch of Momentum, grant type funding for artists was very rarely considered as an option.

Attitudes are very different when it comes to sport. Even world-class athletes such as Mo Farah continue to receive grant funding from Sport UK. In Farah’s case, this is despite considerable endorsement income and a personal net worth rumoured to be £4 million. Grant type funding in sport began in the late 90s. Twenty years later, Great Britain can look back on Olympic glory over the past three Olympic cycles in Beijing, London and Rio across a range of sports. This was no coincidence.

THE ROAD AHEAD

Leading up to the publication of the government’s Industrial Strategy (Creative Industries Sector Deal) earlier this year, there was much debate about funding. Early funding gaps were evident across the creative sector and especially so in music.

For a new artist, releasing music has never been easier: the major streaming platforms are readily accessible to any artist. The principle sources of investment remain labels and publishers although other self-release options such as Seed EIS are available. What has changed is the time it takes to reach that level. A new artist may take several years funding their own releases and live shows during that time. Few new artists have the means to do this, especially those from less affluent backgrounds. This has created very real roadblocks in the talent pipeline as the industry has shifted from CD to download to streaming.

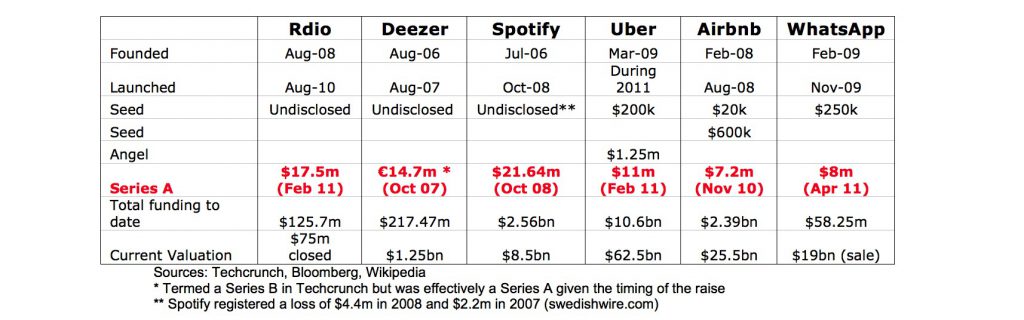

There is a clear deficiency in investment at the seed/ angel level. Unlike the tech world, there are very few mechanisms providing a return to the early stage investor while safeguarding the artist. An artist’s business structure, especially at an early stage, can be fluid and may not have all IP and activities sitting in one entity. Very few new artists could be considered “investment ready” in a traditional sense.

This is why grant funding is so important. It does not require equity stakes or convertible loans. It is simple and when targeted correctly, as Momentum has proven, can be highly effective. Grant funding can play a central role in growing a sustainable talent pipeline that fits the streaming age that is now upon us and ensure the industry picks more winners.

The disproportionate level of Arts Council funds devoted to opera does not seem fair or sustainable and it would seem this is recognized even within the world of opera. Meanwhile, the music industry has proven that grant funding can provide a significant boost to more popular genres and sustain a diverse pipeline of creative talent that works in tandem with existing commercial models. Making the numbers work is a bigger question, but there would seem to be a clear imperative to develop a fairer and more balanced approach to Arts Council funding for music.