This article first appeared in Music Business Worldwide, which you can view here.

Oh no, not another YouTube article! There has been so much back and forth over the past few weeks. My personal favourites are David Balfour, Nelly Furtado and Irving Azoff – all of whom have put forth compelling arguments on the music side. Christophe Muller and Robert Kyncl (pictured) have argued YouTube’s corner.

As someone with a foot in both the music and tech what strikes me time and again is the two sides frequently speak at crossed purposes, as appears to be the case with YouTube and the music industry.

This article weighs up where common ground might exist and how both sides might work together once matters are resolved.

To be clear: my personal opinion so far as the value gap, etc is concerned is broadly in line with Azoff et al, but nor do I see YouTube as the “devil”.

So here goes:

1) YOUTUBE: THE NEW BROADCAST PARADIGM (BUT NOT NECESSARILY RADIO!)

The impact of YouTube goes way beyond the music industry. It seems an entire generation is turning away from traditional broadcast media, eschewing satellite and cable subscriptions and even television sets altogether in favour of phones, tablets and laptops with a super-fast broadband connection.

Against this backdrop, native YouTube talent has reached global scale without the help of traditional media.

A number of articles document this trend including this one and this one.

YouTube presents a massive opportunity for artists at all levels, but that opportunity – as things stand – is not the same as fully licensed streaming services.

“A HUGE AMOUNT OF MUSIC IS CONSUMED ON YOUTUBE BUT, OVERALL, IT IS PRIMARILY A PLACE WHERE CREATORS ENGAGE WITH THEIR AUDIENCE.”

A huge amount of music is consumed on YouTube but, overall, it is primarily a place where creators engage with their audience and present their personality, vibe, brand, or whatever it is they want to put out there.

Take a YouTube channel for any given artist. There will be a number of music videos uploaded over a period of time, maybe some audio tracks and hopefully a decent number of subscribers to that artist channel.

Now go into Content ID, block all the music content completely and instead feed the artist channel’s subscribers with a regular stream of vlogs, interviews and docu-footage all filmed and edited on the fly with a GoPro on a shoestring budget.

All of this is monetized through a variety of ad strategies available to YouTube creators.

It would take a brave artist/manager/label to make such a move, but supposing this resulted in more subscribers, more viewing time and more revenue? Even better, it does not require the use of highly prized music rights currently undervalued by the existing YouTube model.

This is not as absurd as it might sound.

2) THE CURRENT GAME AND HOW TO MONETIZE YOUTUBE

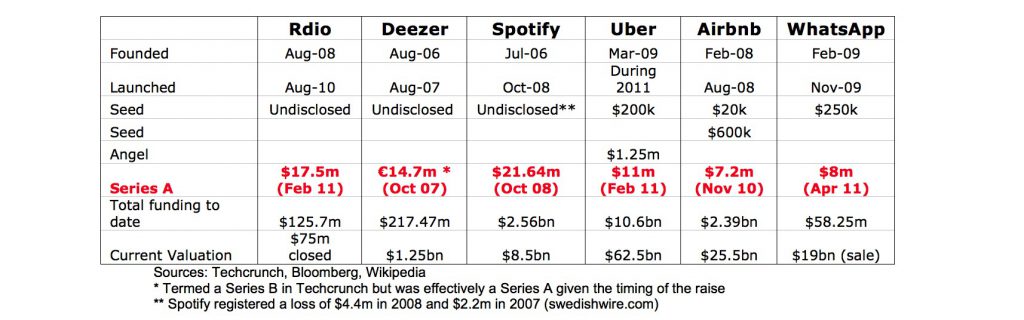

MBW notes that YouTube paid out $634m to music rights holders; but if music content makes up a third of all views, surely that figure should have been $1.6bn?

Here’s why: YouTube is not optimized for Total Views, it is optimized for Watch Time, which is about user engagement and encouraging users to stick around and watch more content. Channel subscriptions have a huge impact on Watch Time and as Mark Mulligan notes, music massively underperforms on channel subscriptions relative to other creators and especially native YouTubers.

If the typical artist channel only refreshes with three new videos every eighteen months or so, even if those videos clock up big viewing numbers it is no surprise revenues underperform (under the current model). Not enough advertising inventory is generated if users click on a music video and then click away.

In contrast, native YouTube creators constantly drip feed content, engaging with and growing their audience, encouraging them to keep watching their channel. This in turn creates more advertising inventory and more revenue.

“NATIVE YOUTUBE CREATORS CONSTANTLY DRIP FEED CONTENT.”

One YouTuber told me she quit her day job once her channel reached 60,000 subscribers as by that time she was earning enough from her channel to sustain herself. She did not have an MCN or a manager, only an agent for brand work.

Another YouTube channel I know has grown to 700,000+ subscribers. Its revenue supports a team of seventeen fulltime staff and fresh content is uploaded several times per week. There are plenty of similar success stories.

These channels follow a formula. There are no dark secrets; insights on how to make the most of the platform are there for anyone who cares to look. This approach is not right for every artist, but there are plenty of permutations for creative individuals to engage with their audience in their own style.

3) THE FOOT SOLDIERS “GET IT”

While senior YouTube executives trade blows with music industry figures, those closer to the coalface are doing some great work.

Within YouTube there is a global content partnership team. They run workshops and presentations for artist managers and provide a point of contact for rights owners of all shapes and sizes. Many are ex-music industry people.

On the label side, I speak to industry colleagues with lots of ideas to better monetize their artist’s YouTube channels.

“MANY REMAIN DEEPLY SKEPTICAL OF A PLATFORM THAT DOES NOT YET DELIVER FAIR MARKET VALUE.”

This requires buy-in not only from their label bosses but also managers and artists, yet many remain deeply skeptical of a platform that does not yet deliver fair market value for music assets. Once that skepticism is overcome, however, great things can happen.

One recent independent label client of mine doubled its YouTube revenue in less than a year purely through optimizing content and applying best practice across its artist channels. There are similar stories elsewhere for both artist managed and label managed channels.

The caveat is this: these revenues are substantial in the context of UGC generated content, but fall well short of the rest of the fully licensed streaming market.

4) EVOLVING THE BUSINESS MODEL

What is most striking about the current situation is that while YouTube’s business model very clearly does not work for the music industry as far as its traditional assets are concerned, it could be argued it does not work for YouTube either.

If music content is only generating $634m on YouTube when it should be making at least $1.6bn (current model), surely that should also be an issue for YouTube?

What is holding YouTube back from coming to the table? They appear fearful not only of paying a market rate but also limiting functionality for music assets in line with other, fully licensed ad-funded services.

Many observer’s comment that YouTube’s parent company, Google, is more concerned with data mining based around search rather than building a content business for YouTube. Search is the business Google knows best after all.

But what if YouTube could be persuaded to step out of its comfort zone and properly incentivize rights owners? Two things could happen:

- Artists and labels may be more disposed to invest more in their own UGC content and deploy content strategies similar to native YouTube creators.

- Up-selling to subscription services and possibly even a la carte services.

The latter point should be a no-brainer. Spotify has shown freemium is an effective funnel to higher value services and YouTube offers one hell of a funnel. Moreover YouTube already does this for TV and movies giving users options to rent or buy, as they can on fully licensed platforms. No wonder the music industry feels left out.

The former point is a significant opportunity not apparent to many music industry executives largely skeptical towards ad-funded business models generally and the current YouTube model specifically. But if YouTube came to the table and engage more positively they can win over the skeptics and build a substantial business within the music vertical on artist UGC content alone. On top of that is an even bigger business around premium content in one form or another.

5) MAKING THE NUMBERS WORK

In bringing all of this together, the broader opportunity needs to be understood. YouTube’s Robert Kyncl is underselling the potential of his platform when he says only 20% of consumers have ever been willing to pay for music. This is wrong.

Figures I have for the pre-digital era indicate that 20% consumers bought at least one album per month or more, a further 30% 1-2 albums per year and only 50% of consumers never bought music, not the 80% Kyncl suggests.

“IN THE DIGITAL AGE, SURELY THE GOAL MUST BE TO ENCOURAGE MORE PAID CONSUMPTION – NOT LESS?”

These are Gallup/ BPI figures for the UK market in the early 90s (which I relied on for my undergraduate dissertation on digital music written in 1993).

This was before mass-market retailers entered the market and CDs still sold at a premium. As the decade unfolded per capita consumption, if anything, increased. In the digital age, surely the ultimate goal must be to encourage more paid consumption not less?

Ad-funded services have a part to play, but the opportunities to up-sell are much broader, but also more granular. YouTube is an ideal platform to exploit that granularity and hopefully YouTube Red might unlock some of those opportunities.

WHAT NEXT?

YouTube is far too random a proposition for one business model. It is a pick’n’mix of traditional content creators, native YouTube creators and pure amateurs.

Artists and rights owners, meanwhile, have not tapped into what YouTube does best: monetizing artist and label channels with their own UGC.

Both sides need to step out of their comfort zones. That requires YouTube evolving its business model with strands and layers appropriate to vertical markets such as music.

It also requires further diversification from artists and rights owners to create and monetize their own UGC programming.

That is where the common ground lies.