This article first appeared in Music Business Worldwide, which you can read here.

The digital music market continues to grow, but life remains tough for music tech start-ups. Rdio bit the dust before Christmas and Cür Music, had a fight on its hands to meet payment deadlines to labels, which it has now done. Even some of the bigger players are not without their problems as MBW has alluded to.

Many within the music industry have little sympathy for the tech sector, yet the fact remains hardly any fully licensed music start-ups have achieved either profitability or a successful exit after almost twenty years of trying. It is worth asking, why?

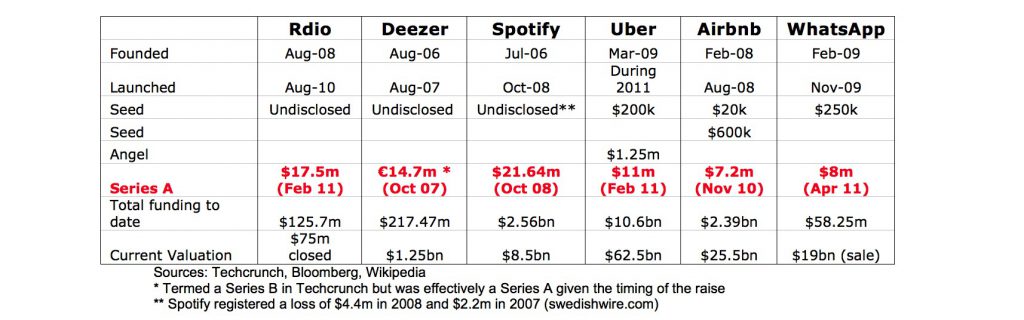

The table below compares the biggest music tech start-ups of recent times against three of the biggest tech start-ups overall during the same period. It compares their launch dates, early fundraising and current valuation.

The Series A is the key line to focus on.

This is the funding round that enables a start-up to launch its product or to scale to a meaningful level once in the market through hiring a team, product development, marketing, etc.

Rdio, Deezer and Spotify required a Series A funding round that was more or less double the Series A for three of the most successful start-ups of recent times.

Spotify is by far the most successful music tech start-up in terms of scale and impact. It was founded in 2006, launched in late 2009 with a Series A of $21.6m. On this funding round Spotify concluded deals with all three majors and Merlin. Reports suggest the company burned through $8m prior to the Series A, so Spotify was $30m in the hole pre-launch.

Compare this with Uber, AirBnB and WhatsApp and some interesting points emerge:

- All three raised much smaller Series A rounds, less than half what Spotify did.

- AirBnB and WhatsApp launched two years before raising their Series A, valuable product development time in the market prior to scaling properly.

- These companies are superstars, yet their initial steps were broadly in line with most start-ups. The typical Series A round falls within the $2-10m range,

- AirBnB launched in 2008 with an initial Seed round of $620k, waiting over two years to secure a Series A of $7.2m.

- Uber and AirBnB have valuations far in excess of Spotify’s while WhatsAppachieved an exit more than double Spotify’s recent valuation.

Even leaving aside the headline grabbing unicorns (the billion dollar start-ups), a more typical goal for a founder or investor is a $100m+ exit.

Over the past five years, there have been around 100 or so tech start-ups achieve such an exit per year either by IPO or acquisition.

These include SaaS, FinTech, AdTech Social Media start-ups but no music tech start-ups and certainly not ones that are fully licensed.

Asking around amongst well-placed friends, who have held senior global digital music roles, between us we can only think of two successful exits for music services in the past fifteen years or so:

- MusicMatch selling to Yahoo for $160m in 2004

- Last.fm selling to CBS for $280m in 2007

Last.fm was not fully licensed but a number of rights owners managed to close deals around the time of the acquisition.

So that means only one fully licensed music start-up has achieved a successful exit and that was in 2004!

What would you do if you were a founder or early stage investor? Go for music and swallow greater dilution of equity with greater financial risk? Or target other sectors that require less dilution with less risk and, potentially, offer a much greater return?

Bootstrapping and lean start-up methodologies have been widely adopted within the tech sector. Yet, applying these methods to music tech start-ups is problematic.

The benefits of the lean start-up model are very simple: eliminate waste and focus on product development. Build, measure, learn and repeat in short iterations until the product is sufficiently developed to scale. Balance the risk and pick more winners.

The business development model that rights owners apply to licensing digital services is well established (equity, advances, minimum rates, etc). Yet this approach places a huge burden on music tech start-ups before they even launch.

In fairness to the music industry the tech mantra of scale first, establish a business model second should be given short shrift. No AirBnB host would want to give free accommodation to strangers just to help out some tech entrepreneurs. Why should rights owners give anyone a free lunch? They should not.

Streaming is fuelling a growth in recorded music revenues but there is still a long way to go to get the market back to where it once was let alone to where it could be.

Moreover, the market is dominated by a handful of major tech players. Yet corporate tech companies cannot always be relied upon to innovate. In the music tech space for every Apple there is a Mircosoft or Nokia that does not quite hit the mark.

Time and again, start-ups innovate and create new markets across a range of industry sectors. The music sector, however, remains problematic.

Leaving aside the actual deal structures for music licensing, the costs associated with negotiating the deals, managing content and reporting usage are substantial whichever side of the table you sit on.

Of course, some would point to Blockchain and GRD as solutions, certainly the tech industry has proved adept at collaborating at an infrastructure level to enable more innovation in the market.

Facebook helped established the Open Compute Project that has signed up just about every major tech giant except Amazon. The reasoning is very simple. Tech giants are not competing on their server capacity, they are competing on the next wave of innovation around VR, AI and so on that sits on top. So collaborate on the back end to enable a higher level of competition where it matters. Brilliant thinking.

In fairness to the music industry, it has picked up the mantle to fight online piracy and address issues such as the value gap and safe harbour. Such work creates a fairer environment for innovative music tech start-ups seeking to launch fully licensed legitimate digital music services. This is something the tech community, as a whole, should recognise.

Coming back to the music tech start-up looking to strike deals with rights owners, how might the business development teams approach these opportunities and back more winners?

For the sake of brevity, let’s consider three key components: cash, equity and debt.

Ask for too much cash upfront and the start-up struggles before it even gets going. To the extent at advances are applied, many observers say advances should be proportionate to the likely earn through especially in the early stages.

Entrepreneurs often complain this does not happen and advances can be too aggressive. But what is the alternative? Cash is less risky and if rights owners are assuming more risk, then the overall compensation should reflect the level of risk.

Equity is well established in licensing deals, usually on the first round of negotiations and that equity dilutes over further funding rounds until a final exit is achieved. But only one such exit has ever been achieved.

How might the equity piece be approached differently? Perhaps there is an argument to take more equity earlier, divest a proportion of that equity on later rounds and retain the remainder until final exit?

Such arrangements are not that common but do happen. There are all sorts of permutations.

Debt finance is often overlooked, but it has been brought into prominence on account of Spotify’s latest funding round. The debt piece can be structured in all sorts of ways, interest can be applied and it can be converted to equity on pre-agreed terms. For a start-up low on cash, it is an alternative, but it is still risky for the rights owner.

These thoughts just skim the surface of a complex problem, but a problem exists and it affects all of us in the digital music value chain. There are no easy answers.

Provided the start-up is on the hook one way or another for the music rights they use from day one, are there more creative way to strike these deals to enable more innovation and growth in the digital music market?

If Spotify does achieve a successful exit, then it will only be the second fully licensed music start-up to do so. We need more.